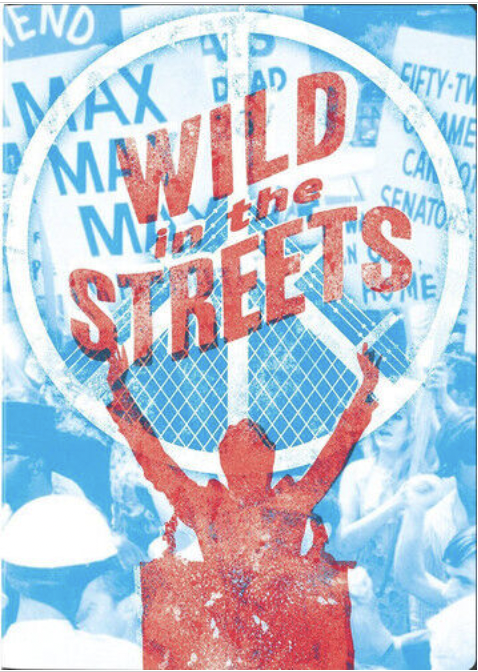

Max Frost For President - Put This Country On The Right Trail

Potencial Pot Party Locations

Slumming -The theaters and taverns on the Bowery attracted many tourists to the Five Points neighborhood, and many upper-class people popularized “slumming.” Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Davy Crockett and Charles Dickens ventured into the neighborhood to observe depravity and soak in the slang and fashions of the many gang members. Sometimes they peeked in with police escorts, other times they brought friends. Dickens liked to go to Pete Williams Place, an African American dance hall originally called Almacks Dance Hall. Here at 67 Orange Street (now named Baxter), just south of Bayard Street, Dickens observed a dance called a break-down that blended Irish jigs and reels with African shuffle. The masters of this dance, which grew into tap dancing, included William Henry Lane and Master Juba. This music hall venue led to the blues, jazz, and eventually rock and roll. Dickens wrote about this dance hall and neighborhood in his 1842 work, “American Notes.”

The Tea Water Pump, the source of the freshest and most famous water in Manhattan, is now guarded like Fort Knox with 24-hour police protection. The old gardens that used to be here have been replaced by a small, inaccessible patch of green that has an old, spooky concrete shack next to a strange sculpture apparently covering the old well.

Old Wreck Brook flowed just south of Roosevelt Street (east of Baxter) from the Collect on Centre Street. The brook once entered the East River at the foot of James Street (just south of Catherine) and was also called Ould Kill and Versch water. This brook had the freshest water and was tapped at the Tea Water Pump on Park Row and Baxter. The Manhattan Company doomed the tea water pumps and any attempt to construct a more reliable supply.

Dog carts once pulled water from clean wells and pumps and took away garbage, and they were prohibited from NYC streets in 1870.

Kissing Bridge - NYC's first Kissing Bridge crossed the Old Wreck Brook (also called Tamkill Creek, Ould Kill and Versch Water) just south of the old Roosevelt Street (east of Baxter). This old bridge was used to get from Park Row to the Bowery. The brook had the freshest water and was tapped at the Tea Water Pump on Park Row and Baxter. The Kissing Bridge was an early NYC bridge crossing the high area on Park Row between Collect Pond and Beekman's swamp. It was the first NYC bridge to be called the Kissing Bridge, the second was the Stone Broadway bridge over Canal Street (also called the Stone bridge), and the third, at 77th Street and 3rd Avenue, became NYC's most famous Kissing Bridge.

The old brook that led up Roosevelt Street to the old Collect Pond still discharges in spurts into the East River during part of the day. The old NYC shoreline came up to Cherry Street, and the largest cove in lower NYC was close to NYC's first kissing bridge.

The name Old Wreck Brook could have originated with Adrian Block’s boat, the Tiger, after it caught fire at night while docked in a cove off lower Manhattan. This supposedly happened right off the Hudson River coast next to what much later became the World Trade Center site, but I believe his boat caught fire off the East River by the Collect Pond stream, its burned-out wreck of a hull remaining to suggest the name. He could have camped for the winter at the old ruins of Norumbega with access to plenty of fresh water from the Collect Pond and fish, foot-long oysters, clams, and lobsters galore.

The area around Collect Pond was so low that during spring floods, Indians could paddle across NYC from the Hudson River through the stream where Canal Street is now to the the Pond.

Tamkill Creek flowed under the kissing bridge that flowed from the Collect Pond by Park Row and Roosevelt Street.

John Kenzie's Ranelagh Gardens - Starting in 1765, Ranelagh Gardens was a NYC summer garden named after a famous London resort sitting on a 40-acre hill once called Kalckhook Hill. To attract British soldiers during the American Revolution, John Kenzie advertised the Ranelagh Gardens as a rival of the New York version of the Vauxhall Gardens, also named for a famous London resort. It worked; British officers used Ranelagh Gardens as their headquarters, where they entertained some of the 3,000 prostitutes sent overseas to entertain the troops.

For 20 years this pleasure resort called Ranelagh Gardens was leased by John Jones, who used Colonel Rutgers’ 1730 mansion and garden near the west side of Broadway and Thomas Street (between Duane and Worth Streets). The original Vauxhill Gardens folded because of the classier, more elegant Ranelagh Gardens, which was also more accessible. These flowery resorts served afternoon tea and other refreshments, had dancing platforms, and offered vocal and instrumental band concerts and fireworks. Tickets to enter Ranelagh Gardens cost about 2 shillings each.

Before the gardens, the area was a swampy wetland leased by Anthony Rutgers, who a year later got the title to the land and built his mansion in 1730. In addition to roadhouses and pleasure resorts such as Vauxhall Gardens and Ranelagh Gardens, this one-time aristocratic neighborhood, formerly part of Lispenard's Meadows, became overrun with taverns, also known as mead gardens.

The Ranelagh Gardens closed in 1793 to become the site of the New York Hospital.

Chambers Street Wall - In 1653, Wall Street actually had a wall that followed a fence to keep animals from the crops outside the city limits. The wall was erected to address the threat of New England attacks on the old city that was packed together south of Wall Street (they never anticipated attack from British ships).

This famous Wall Street wall was not the only wall in NYC's history; the city was actually walled twice. A few years after the military started using City Hall Park for a parade ground in the 1730s, NYC created its second wall in 1745, a year after the French declared war on the British. This palisade of 14-foot cedar logs zigzagged across NYC from the foot of Chambers at the Hudson River (still called the North River at that point) to just north of Mr. Desbrosses’ house at 57 Cherry Street by the East River. The Desbrosses house was the northern-most home in NYC limits at the time (before the Kips Bay homes). The wall went westerly from the Desbrosses house to Katy Munz's home by Catimut's Hill, and then just north of Chambers Street to the North River (Hudson). Katy Munz was known as Aunt Katy and had a tea garden between Pearl and Chatham (Park Row) Streets, just east of Gallows Hill.

Besides a barricade against the French, this second wall also protected the town from angry Indians who didn't take slaughter lightly. Thanks to blunders by governors such as Willem Kieft's February 25th, 1643, slaughter of Native Americans at Corlear's Hook and Pavonia (Jersey City), NYC was only too aware of the hostility in the air.

One of the Chambers Street wall’s six blockhouses was on the site of A.T Stewart's Marble Palace on the NE corner of Broadway and Chambers. The gate at this main blockhouse allowed entry to Broadway by City Hall from the wilderness on the other side. The six blockhouses had portholes for cannons. There were four strong gates on the Chambers Street Wall, Broadway, Greenwich Street, Pearl Street and the Post Road (Park Row, then called Chatham Street). Other blockhouses were situated at Pearl Street by Madison Street (then called Bancker), and by Chambers between Church and Chapel Streets (West Broadway). Within the wall was a four-foot high by four-foot wide platform where soldiers could shoot their muskets through perforated holes to defend the city.

Hall of Records -A Beaux Arts-styled building built between 1899 and 1907 at the NW corner of Centre Street, 31 Chambers Street was the old Hall of Records, and the structure since 1962 has been called Surrogate's Court. Construction cost $7 million and has housed the Municipal Archives since 1950. The archive’s collections of over two million pictures and photographic items date back to the early 17th century and take up 160,000 cubic feet of space. It is America’s main source for family history. Since 1984, its master records, drawings, manuscripts, negatives, certificates, books and photos have been copied onto silver-halide microfilm and taken off-site to a secure, climate-controlled facility. These second generation research tools are used for public access in the Municipal Archives Reference Room and for interlibrary loaning. These records would one day also make many great city-based apps.

The Rotunda -Built in 1816, to the west of the City Dispensary and east of the second Almshouse, the Rotunda opened in City Hall Park's NE corner in 1817. The Rotunda’s circular building housed NYC's first Art Museum, and it was often referred to as the Round House. Artist John Vanderlyn could use the Rotunda for nine or ten years rent free after it was built for his own personal showroom, but after that the building would become the property of NYC. It was paid for with the help of $6,000 contributed by 112 of his supporters. A protégé of Aaron Burr, Vanderlyn painted panoramas of Geneva, Paris, Athens, Mexico, Versailles Palace and Gardens, and even a few battle scenes for NYC's first art museum. He was the first American painter trained in Paris, where he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts. John Vanderlyn died in Kingston, NY, Sept. 23, 1852.

After the Fire of 1835, NYC used the Rotunda as a post office for 10 years. The New York Gallery of Fine Arts used it until July 24th, 1848, when they were told to vacate, and the building was turned into public offices. The Rotunda was enlarged and squared off, lasting until demolition in May 1870. By the time it was razed, the Rotunda was flush against the Tweed Courthouse to its west and an alleyway between the firehouse to its east. One of the last tenants was the Croton Aqueduct Board, which had offices in the Rotunda for 20 years.

Bixby's Hotel - Bixby's Hotel at 1 Park Place at Broadway became famous in the 1850s for the writers who would gather to discuss the topics of the day. Nathaniel Hawthorne would huddle around Daniel Bixby's stove on his infrequent visits to NYC. Bixby was a publisher who set himself up as a hotelkeeper to cater to journalists. Naval officers also frequented his hotel. On May 4th, 1852, Edward B. Crane hung himself from the bed post at a 4th story room at Bixby's. According to his suicide note, Crane a resident of Millville, Massachusetts didn't get the courage to jump overboard from his boat so he took the hotel room and his life. Crane's note claimed that it took more courage to live than to die.

William Mooney -Barden's Tavern - After owning his first inn in Jamaica, Long Island, Edward Barden, a veteran, opened a tavern on lower Broadway in Manhattan that may have the birthplace of Tammany. In late 1786, the Tammany Society (also called the Columbian Order and the Independent Order of Liberty) was founded by upholsterer William Mooney, who had been active as one of NYC's Sons of Liberty. The society most likely started at Talmage Hall because later meetings were advertised at that usual location.

At Barden's Tavern, on the corner of Broadway and Murray Street in 1770, a club of lawyers called the Moot met on the first Friday night of each month. And here on May 12th, 1789, the Secret Society of St. Tammany was founded as a political and social organization under a constitution and laws. Also the first Grand Sachem of Tammany, Mooney and some of his craftsmen companions wanted the Tammany Society to provide the common soldier a club as nice as officers’ clubs. In 1788, Barden took charge of the old City Arms on Broadway and Thames Street, so the Tammany meetings at Barden's were held not at Murray Street but further downtown on the west side of Broadway This makes sense as one of the known gathering spots of Tammany Society at that time was on the banks of the Hudson. Tammany called Barden's Tavern their wigwam, and members wore Indian costumes to the meetings until 1813. Tammany was regularly incorporated as a fraternal aid association in 1805.

Talmage Hall at 49 Cortlandt Street was believed to be the site of St. Tammany Society’s earliest known annual wigwam, May 1st, 1787, to honor the society’s saint, the legendary immortal Tammend, a Delaware chief, “great in the field and foremost in the chase.” The event was written up in the press making May 1st, St. Tammany's Day, and likely the initial function. Society that became a political machine that became the Democratic Party. It controlled NYC politics while helping millions of voting immigrants (especially the Irish). Members’ ranks in the club were named using Indian titles ranging from Braves to the highest level Sachems. At one time, only male property owners were allowed to vote in political elections until Tammany opened voting to all men. Their other progressive ideas ended debtors prisons.

The first meeting of the directors of the Manhattan Company, Aaron Burr’s water utility concern, was held at Edward Barden's Tavern on April 11th, 1799.

James Fenimore Cooper -Bread and Cheese Club - Born September 15th, 1789, in Burlington, NJ, James Fenimore Cooper became one of the most popular American novelists. Besides his famous "The Last of the Mohicans," Cooper’s novels include "Precaution," "The Pioneers," "Lionel Lincoln," "The Prairie," and “The Pilot." In 1822, Cooper created an informal social and cultural conclave called the Bread and Cheese Club (also called "The Lunch" and the "Lunch Club" by its intimates). It grew out of impromptu gatherings of Cooper's intellectual network of friends. Membership consisted of American writers, editors and artists as well as scholars, educators, art patrons, merchants, professionals, lawyers and politicians who dabbled in the arts. The chief shared aim of their forum was to enhance America's cultural independence. The club was organized around the notion of an electoral system in which prospective new members were voted in with bread, or rejected with cheese.

The Bread and Cheese Club first met in the back room of Wiley's New Street bookstore on the corner of Wall and New Streets. Before moving to New Street, Wiley opened his first print shop in 1807 at 6 Reade Street. John Wiley was the publisher who made Cooper a national celebrity when he published his second novel, “The Spy,” in 1821. The Bread and Cheese Club was first called “Cooper's Lunch," which was an outgrowth of the back room at Wiley's called "The Literary Den.”

The Bread and Cheese Club would hold most of its meetings at Washington Hall, which stood on the SE corner of Broadway and Reade Street. The members would generally meet every fortnight (14 days) on Thursday afternoons until the evenings after dinner. Food for the suppers were supplied by members on an alternating basic and usually cooked by Abigail Jones, an artist of color. Members took turns catering or hosting the meetings, assisted by daughters of members. Of the members’ total of 73 daughters, Cooper had five. He also had two sons with Susan Augusta DeLancey (1792-1852), whom he married January 1st, 1811, in Mamaroneck, NY. After living in New Rochelle, NY, the Coopers moved and built a home in Scarsdale.

Besides Cooper and his publisher John Wiley, the club’s membership of just 35 included poets William Cullen Bryant, Fitz-Greene Halleck, J.A. Hillhouse, and Robert Charles Sands; writers Washington Irving, James Kirke Paulding, J.G. Percival, Major Jack Downing, and Gulian C. Verplanck (also an editor and lawyer); painters Thomas Cole, William Dunlap, Asher Brown Duand, Henry Inman, John Wesley Jarvi, John Vanderlyn, Robert Weir, and Samuel Finley Breeze Morse (also an inventor); artist R.S.A. Durand; merchants Charles Augustus Davis, Jacob Harvey, and Philip Hone; businessman James DePeyster Ogden; judges William Alexander Duer, John Duer, and Chancellor James Kent; naturalist James Ellsworth De Kay; physician John Wakefield Francis; editor and educator Charles King; philosopher James Renwick, and author-lawyer Henry Dwight Sedgwick. Another author, Edward John Trelawny, only visited the club, and there were another two members whom history books have deleted.

In 1824, when he was living abroad, Washington Irving was made the Bread and Cheese Club’s honorary chairman in absentia. Also that year, another member, painter (and inventor) Samuel F. B. Morse entered NYC's competition to commemorate the Marquis de Lafayette's tour of the U.S. Morse's official portrait of the Marquis won the prize. The Marquis de Lafayette was greeted by Cooper's Bread and Cheese Club in 1824 before traveling with General Swift to West Point.

The Bread and Cheese Club lasted while Cooper lived in New York City until 1826, when it branched off into the Sketch Club and the Literary Club in 1827. Cooper died in 1851.

Bridewell Debtors Prison -On March 17th, 1775, the Common Council approved plans for the new city prison, the Bridewell. The main building of the Bridewell and its workhouse was finished in April 1776 and stood between the site of the first Almshouse and Broadway until 1838. With just bars in the windows and nothing to stop cold winds, the dark grey stone Bridewell building had a middle structure three stories high and wings that were only two stories. Besides vagrants, the mentally ill were also locked up in because mental illness was seen as a social problem at the time.

During the British occupation from 1776-1783, American POWs were housed in the Gaol and Bridewell, starting with Colonel Robert Magaw's captured garrison of 1,200 men from the badly planned Battle of Fort Washington (November 16th, 1776). The Battle of Fort Washington was known as the Alamo of the American Revolution. Only 59 Americans died in the British attacks from the south, east, and north. George Washington thought to abandon the fort and move the men to the safety of New Jersey, but General Nathanael Greene convinced him to defend it. Magaw walked away in a prisoner exchangd for another high ranking British officer, but most of his men died in the prison ships in Wallabout Bay. After surrendering to the British, 2,837 Americans walked downtown to their death or imprisonment for the duration of the American Revolution. On January 4th, 1777, 800 men filled up the Bridewell Prison, which led British doctors to administer some kind of poison powder to keep the prisoner numbers down.

Forgiveness of debt came to NYC thanks to Tammany Hall and reformer Joseph D. Fay, who led a crusade with the message that debtors don’t suffer from moral failure but are just victims of downward business cycles. In 1831, jail sentences for insolvency finally became forbidden in the State of New York. (In England, Parliament didn't end debtors prisons until 1869.) This law ended the 55-year-run of the Bridewell Debtors Prison and established the word “bankruptcy.” Almost two out of three immigrants who arrived in America were debtors on arrival.

When the Bridewell was demolished in 1838, some of its stones were reused to build the original Tombs Prison, under construction the same year. The first Tombs Prison held 150 men and 50 women in its poorly land-filled, sinking structure. The land the Bridewell would sit on was owned by John Lamb and the Sons of Liberty, who bought the land in 1770 to erect a Liberty Pole that was inscribed “Liberty and Property.“ After the Battle of Golden Hill, other Liberty Poles went up on this spot across from 252 Broadway.

Brom Martling's Tavern - Tammany members back in the day would dress in Indian garb for some of their ceremonial events and meetings, where they smoked the calumet, or peace pipe. The first wigwams they rented consisted of the long room at Brom Martling's Tavern, the City Tavern, and Fraunces Tavern (NE corner of Pearl and Broad). Before, their usual spots included Talmage Hall and Barden's Tavern.

From 1798 until 1812, Tammany Hall organizers (frequently called Martlingmen) met at Abraham Martling's one story tavern (SE corner of Nassau and Spruce Streets), before moving to their own building (the first Tammany Hall) on the west side of Broadway between Thames and Cedar, by City Hall. This rundown building that was known as the first real Tammany Hall was called the Pig Pen by many citizens. Tammany managed to gain power by keeping a finger on the pulse of the people in taverns. Despite attacks from moralists and crusaders, Tammany survived because its political machine protected the common man and gave him an identity. Many working class immigrants were attracted to Tammany's opposition to nativism and anti-Catholicism. Tammany was founded on the true principles of patriotism guided by motives of charity and brotherly love. Its purpose was to afford relief to the indigent and distressed, but as history has uncovered its evolving corruption, Tammanys must have been guided by the notion that charity begins at their own home.

Tammany was named after Tamanend, the leader of the Delaware Lenape Indians who lived on the banks of the Schuylkill River. Brave chief Tamanend loved freedom and was the subject of widespread folklore. Tammany Society started as an offshoot of a Pennsylvanian club that began in the 1770s. After George Washington's inauguration, the New York chapter of Tammany was started in May 1789 as a patriotic fraternity similar to the Elks or Moose Clubs. Tammany started as a social drinking club for guys devoted to the rights of people to live free in a country without radical or fanatical principles.

Byram’s Garden / Mount Vernon Garden - Before 1796, William Byram ran a public garden and pleasure resort on Kalckhook Hill (just west of Broadway and Leonard Street) known as Byram’s Garden. In 1796, the establishment became Corre's Garden, which was run by French cook Monsignor William Corre. Formerly a chef for a British officer, Corre sold mead and cakes at a stand on the Battery that was decorated with colored lamps. When Broadway was created, the garden towered high above street level and had to be reached by a long flight of steps.

On July 19th, 1800, Corre renamed his garden the Mount Vernon Garden, and a few years later he called it the Mount Vernon Gardens Theatre. As the Park Theatre was closed in the summer, the public was hungry for theatrical representation so Corre's gardens offered cheap concerts, nighttime theatre presentations, and his renowned flying horses, an early cross between a flying swing and a merry-go-round. The flying horses were similar to an eight-person ride Phineas Parker created in the summer of 1800 for Joseph Delacroix's New York City Garden. Parker called the 20 mph rides the Patent Federal Balloon or the Vertical Aerial Coachee.

In October 1800, Corre invited Richard Crosby to lecture on the science of aerostation, and after two weeks he filled a giant silk hot air balloon with inflammable air at the Mount Vernon Garden. Its launching at 4 p.m. on a Monday drew a huge crowd to the garden. Dubbed the beautiful varnished Silk Balloon and Aeronautic Carriage, the balloon rose 400 feet and headed southward until it disappeared from sight.

P.J. Hodges- Carlton House -In 1850, P.J. Hodges ran the Carlton House, a respectable hotel that stood at 350 and 352 Broadway by Leonard Street. Charles Dickens stayed there, enabling him to witness the gritty Five Points district nearby. The Carlton House was just a few hundred feet away from the entrance to the Points at Broadway and Anthony Street (now called Worth Street). On Friday night March 4th, 1842, Dickens and his guides left the Carlton House to go slumming. The Carlton House was originally the home of Stephen Price, who was a joint lessee of the Park Theater, and Thomas Cooper, the tragedian. Another Carlton House was off Frankfort Street by William Street under the Brooklyn Bridge.

City Hall Park - Unlike the Tweed Courthouse costing over $16 million, the third City Hall only cost only $500,000. City Hall was built on a hill looking over the huge harbor that made NYC what it is today. The Commons (City Hall Park) was first used as a park in 1686 by the few hundred people who lived in NYC at the time, a far cry from the 100,000 that occupied NYC by the time the third City Hall was finished in 1811.

Joseph F Mangin (French) and John McComb Jr. (Scottish) designed the third City Hall using a French Renaissance Georgian style. When this City Hall was built, the side that faced north was simply done in brownstone unlike the rest of the expensive Massachusetts marble structure. The reasoning for not using marble on the northern side was that no one of importance lived that far north. In 1831, the first illuminated public clock in NYC was added atop City Hall’s cupola where a fire tower was also built. Huge City Hall celebrations were held for Lafayette, Charles Lindbergh, the Atlantic Cable (whose 1858 fireworks caused City Hall's biggest fire), and the opening of the Erie Canal. On April 24th and April 25th in 1865, Abe Lincoln's body was put in City Hall’s colonnaded Rotunda.

Outside City Hall in 1776, George Washington and his troops listened to the reading of the Declaration of Independence in front of the citizens of NYC.

Abraham De La Montagne-Abraham De La Montagne's Tavern / Montagne Garden and Public House - Headquarters of the Liberty Boys. Located at 253 Broadway on the west side, just north of Murray Street. On January 13th, 1770, British soldiers from the 16th Regiment attempted to blow up the Liberty Pole with black powder. Failing that, they attacked Montagne's breaking its windows and wrecking furniture. A few nights later, on the 17th, the British succeeded in sawing down the Liberty Pole, and it was found in pieces outside the front door of Montagne's. After the Revolutionary War, Montagne changed the tavern’s name to the United States Garden. By 1772, NYC had 22,000 citizens, doubling in size since 1742. There was a tavern for every 55 citizens. Montagne's Inn was taken over by the famous purveyor of ice cream, John H. Contoit, who ran it from 1802-1805. Contoit renamed Montagne's the New York Garden. Augustus Parise then took over the famous site, and after that a new building called the Parthenon was built there.

By the first anniversary of the Battle of Golden Hill on March 19th 1771, the British celebrated at Montagne's Tavern. Abe Montagne must have switched loyalties from all the business from the British soldiers living at the expanded upper barracks across Broadway.

Before all that, Peter Stuyvesant wrote "for want of a proper place, no school has been open for three months, and the youth were running wild," in a bid to inquire about funds for a Latin school. Stuyvesant got his way On April 4th, 1652, when the Directors in Holland agreed to pay Dr. Johannes (Jan) Momie de la Montagne, 200 to 250 guilders a year to start an elementary Latin school at the City Tavern (which became the Stad Huys).

Dugdale and Searle's Rope Walk -In 1719, Dugdale and Searle's long rope-walk stretched along Broadway from Ann Street up to Chambers Street. Thanks to permission from the Trinity Church Corporation, the rope walk lasted for about 20 years at that location in front of City Hall Park. At one point on Broadway, the rope walk ran about 40 feet from an associated small building in City Hall Park across from Murray Street from 1728-1775. This rope walk building I call “hemp headquarters” was removed to make room for the Bridewell in 1775.

First NYC Sidewalks - The first NYC sidewalk was three blocks long on the west side of Broadway between Vesey and Murray Streets. Set in 1787, the narrow sidewalk could fit only two at a time. The first sidewalk on the east side of Broadway was also added in 1787 along the Bridewell fence in City Hall Park.

D.D. Howard - Irving House Hotel -In 1850, the Irving House was a fashionable hotel run by D.D. Howard. It was located at 281 Broadway at the NW corner of Chambers Street, where Nedick's once had a hot dog. After 1856, Delmonicos moved from their first location at 19 Broadway into the ground floor of the Irving House Hotel.

The Irving House Hotel was replaced by the Broadway-Chambers Building (277 Broadway), which was the first NYC project of Cass Gilbert (Woolworth Tower). A Renaissance revival building made of brick ornamented with brightly glazed terra-cotta, the Broadway-Chambers Building was finished in 1900. Its facade is done in a traditional three-part classical composition (tripartite skyscraper construction).

Before it became the Irving House Hotel, John C. Colt, brother of the inventor of the revolver, Samuel Colt, had a second floor office in this building. On September 17th, 1941, John Colt killed a printer named Samuel Adams with a hatchet. Adams had come over from his place at Ann and Gold Streets to Colt's office to collect a $50 debt. Colt packed Adams’ body in a crate, which was taken to the Maiden Lane dock and stashed aboard a ship called Kalamazoo, heading for New Orleans (or South America). Colt was to be hanged at the Tombs Prison at 4 p.m. on November 18th, 1941, but on that morning he got married to his mistress, Caroline Henshaw. A diversionary fire was started in the wooden cupola on the Tombs’ roof, and a burnt body was found in Colt's cell with a knife in its heart. The power of his brother’s wealth and community standing may have made John Colt the first person to escape the Tombs. Rumor had it that John and Caroline Colt made it to France and hid out there the rest of their lives.

Jan de Wit and Denys Hartogveldt's Windmill - Jan de Wit and Denys Hartogveldt built a windmill to grind wheat just south of where City Hall currently stands. The first structure in the Commons, the windmill was followed in 1728 by a small structure built to accompany the rope walk that ran down Broadway from Park Row to Chambers Street. Also on the current City Hall site, NYC's first Almshouse was built by the Common Council in 1734-1736. This first almshouse was frequented by vagabonds, rogues, disorderly persons, parents of bastard children, trespassers, runaway servants and beggars. Just beyond the workhouse fence, it had a cemetery to its east that was uncovered in 1999.

Liberty Tree / Liberty Pole -The first Liberty Pole was put up in Boston on Orange Street by Hanover Square on August 14th, 1765, at which time it was actually a Liberty Tree. Deacon Jacob Elliott's large elm tree was used to hang in effigy Andrew Oliver, a merchant who agreed to collect the stamp tax. Placed next to the tree was a green-soled boot (green being the color of liberty since Robin Hood), which represented the Earl of Bute (who started the idea of the tax). This Boston elm was the first Tree of Liberty, where Quakers were hanged and Tories tarred and feathered. On a flagpole next to it, a red flag was hung to secretly signal a meeting of the Liberty Boys. The name Liberty Boys was coined by a British Lieutenant Colonel Barre to refer to the demonstrators against the Colonial Stamp Act. Sir Isaac started as an Irish soldier and became a Member of Parliament. Barre, VT, and Wilkes Barre, PA, were named after him.

In NYC, when the Stamp Act was repealed on March 18th, 1766, Whigs hatched a plan to erect a Liberty Tree in the Commons (City Hall Park) between Warren and Chambers Streets. This first NYC Liberty Tree was a white pine post, and it was also called the Tree of Liberty. Disturbed as they were by the green symbol of Liberty, the British really got ticked off when the Liberty Tree was cut from white pine, prohibited in general and reserved exclusively for the English Navy’s ship masts.

The first Liberty Tree was put up in City Hall Park on May 21st, 1766, shortly before a banquet on June 6th, 1766, to celebrate the anniversary of the King of England's birth. This tree/pole/mast/flagpole was decorated in the King’s colors. The British wanted to create statues of the King and William Pitt for the anniversary, but the Liberty Boys (by then a group of merchants, seamen, artisans, mechanics and self-made men) objected. British soldiers tore down the first NYC Liberty Tree on August 10th, 1766, causing thousands of patriotic Americans to gather in protest.

After the Liberty Tree, the NYC Liberty Boys erected a Liberty Pole on August 12th (or 14th), 1766, which was torn down September 23rd, 1766. Within a day or two, another Liberty Pole was erected, but this, like all other Liberty Poles, was cut down by the British. Another time was on the night of March 18th, 1767, after being angered by an anniversary celebration of the repeal of the Stamp Act.

On March 19, 1767, less than a year after the first Liberty Tree, 2,000 New Yorkers erected the fourth Liberty Pole, and this one was armored. Heavy iron plates protected the base that was set so deep in the ground the soldiers couldn't topple it. The 1767 Liberty Pole was in response to the Townshend Duty Act (which taxed paint, paper, glass, lead, and tea imports). The Quartering Act made the Whigs wig out, and they began to assault British soldiers as they came out of their barracks. These assaults made the winter of 1769-1770 a very nervous time for the British soldiers.

On January 13th, 1770, the British tried to use black powder to blow up Liberty Pole #4. When this attempt failed, the British attacked Montagnie's Tavern, often used as the Liberty Boys’ Clubhouse as well as Burn's ]]could that name be Burns? If yes, then it’s Burns’ Tavern, wrecking the building and its furniture. British soldiers came back January 17th and sawed down the armored Liberty Pole and left the pieces stacked neatly outside Abraham Montagnie's Tavern at 252 Broadway.

Responding to a Sons of Liberty broadside calling for a meeting on the Commons, 3,000 patriots rallied on January 18th and 19th, 1770. A handbill titled "To the Betrayed Inhabitants of the City and Colony of New York" was written and printed by Alexander McDougall (the leader of the NYC Liberty Boys). The patriots were armed with clubs, brickbats and sharpened sleigh rungs, while the British soldiers had bayonets and cutlasses. For two days NYC was an urban battleground until the military and town fathers restored order.

The whole incident seemed to snowball on January 19th when British handbills titled "God and a Soldier" were put up. Sea captain and privateer Isaac Sears and other Sons of Liberty members tried to stop these postings, and a group of patriots started forming. When they kept a few British troops captive, other British soldiers came to their rescue. The mob of patriots retreated to a nearby wheat field on Golden Hill (between Cliff, John and William Streets). After proclaiming "Where are your Sons of Liberty now," about 40 soldiers from the 28th Regiment charged the mostly Whig crowd with fixed bayonets. Although no deaths resulted from this first significant encounter of the Revolutionary War to come, the injuries made first blood flow and this battle -- the Battle of Golden Hill or Gouden Bergh (Dutch) -- noteworthy.

After the Battle of Golden Hill, privateer Isaac Sears, wine importer John Lamb, African American Joseph Allicocke, and Sea Captain and Liberty Boy leader Alexander McDougall asked the Mayor and the Common Council to erect another Liberty Pole (#5). When they refused, Sears, Lamb, McDougall, and some of the other Liberty Boys bought a plot of land across from 252 Broadway (where the Bridewell would stand), very close to the British Barracks in City Hall Park. This privately owned plot in City Hall Park (then called the Commons) was 11 feet wide and 100 feet deep and was purchased on February 3rd, 1770. Amazingly, this plot was situated near the site of the former Liberty Poles.

On this narrow plot of land on February 6th, 1770, a giant 90-foot pole was erected by the Liberty Boys, 12 feet deep into the City Hall Park ground. This Liberty Pole was the biggest structure in NYC, and it stood for six years, eight months and 22 days. Six horses were needed to pull the 68-foot long lower end (a former ship's mainmast), thousands of armed patriots carried the 22-foot topmast into place. A gilded vane with the word "Liberty" (and maybe "Property" on its other side) was put on top of Liberty Pole #5, and a large flag that said "Liberty" was raised. Inscribed on the pole was "Liberty and Property." Wooden caps, Liberty vanes or Liberty flags were placed on top of most Liberty Poles.

By the first anniversary of Golden Hill on March 19th, 1771, the British held their celebration at Montagnie Tavern (Montagnie must have switched loyalties because of all the British business from the big upper barracks across Broadway). The Liberty Boys bought a building in the Spring Garden on the east side of Broadway at Ann Street (where P.T. Barnum would build his first museum). This new Liberty Boy clubhouse was named Hampden Hall to honor a great English patriot. Somebody tried to topple the pole on March 29th, 1771, but the alarm rallied enough patriots to save Hampden Hall from possible burning and the fifth Liberty Pole survived.

During the March 18th, 1775, celebration of the Stamp Act repeal, patriots gathered at the Liberty Pole were assaulted by a Sergeant William Cunningham (Provost-Marshall during the British takeover of NYC), but this attack failed and Cunningham was punished with a humiliating public whipping. Some of the 11,000 patriots who died under Cunningham's vengeful hands (starving and rotting in converted jails and prison ships in Wallabout Bay) remembered his failed Liberty Pole attack and related this to his harsh actions against them.

Even though the 5th Liberty pole was extra-reinforced with nail-studded iron bars and bound with metal hoops, the British reportedly took it down on October 28th, 1776, under order of Governor Tryon. And it couldn’t have been the first thing that came down when the British first took over NYC after the Battle of Long Island on September 6th, 1776

On Flag Day June 14th, 1921, NYC threw a ticker-tape celebration and put up a new Liberty Pole on the site of the last Liberty Pole of 1776. The exact site was just west of what would later be the Mayor's room in City Hall, in the middle of City Hall’s west side, and Broadway, according to a survey J. Bankers on June 22nd, 1774. Created in two sections just as the last original pole (#5) was, Liberty Pole #6 measured 66 feet tall. A 40-foot lower portion was created from an Oregon Douglas fir tree, a gift from the Lumberman's Association in Portland. The top was made from a Maine pine tree. An exact replica of the old Liberty weather vane was added to the top, and iron bands surround the protected base.

The 1921 Liberty Pole was a joint gift from the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York and the New York Historical Society. In 1940, a replacement pole was erected (#7), but around 12 years later August 29th, 1952, they had to saw it down because of extensive decay. This revolutionary symbol of collective action should always stand in City Hall Park as a reminder of the strength of people power. Standing in City Hall Park today: Liberty Pole #8.

Soldier's Upper Barracks - In 1757, the Upper Barracks (the Lower Barracks were downtown at the Battery) were built at the north end of City Hall Park, near the site of the Tweed Courthouse, by the Chambers Street palisades. The two-story, 420-by-21-ft. barracks building contained twenty 21-sq.-ft. rooms on each floor. During the American Revolution, two more long buildings were constructed for soldiers. In 1784, after the British left NYC, all the barracks were leased for residences and then sold off in 1790.

City Hall Park -City Hall Park is a nine-acre park that once was a free pasture anyone in town could use. It had public bonfires and celebrations five times a year. When it was a livestock grazing area, it was variously called the Flat, the Fields, the Green, the Square, and between 1653 and 1699. it was called the Commons. Hundreds of years before the white man came, an Indian village called Werpoes (werpoe means “hare”) sat just north of City Hall Park. Before the hills of NYC were leveled, City Hall Park was on one of the highest grounds in lower NYC so it had views of the Hudson and East Rivers. The government’s first executions in the Commons took place in May 1691 when Jacob Leisler and his son-in-law Jacob Milborne were hung or beheaded for alleged treason. Leisler led NYC's militia and seized control of Fort James on May 31st, 1689, in the name of William of Orange. Nicholas Bayard got a drunken Governor Henry Slaughter to sign the papers convicting them to death. Before he was executed in the Commons, Jacob Leisler forgave his enemies.

On the site of the current City Hall, NYC's first almshouse was built by the Common Council between 1734 and 1736. The almshouse, which became Bellevue, was a six-bed infirmary used by vagabonds, rogues, disorderly persons, parents of bastard children, trespassers, runaway servants and beggars. The Almshouse, also called the Public Work House and Home of Correction, had a cemetery to its east just beyond the workhouse fence; the cemetery was uncovered in 1999. Also in the 1730s, City Hall Park was used as a military parade ground.

In 1764, the Stamp Act led to the airing of public grievances on the Commons. On November 1st, 1765, the Sons of Liberty’s first activist event took place, and Lt. Governor Cadwallader Colden's carriages and the home of Major Thomas James (Fort George's Commander) were destroyed in rioting that lasted on and off through May 1766 when the patriotic mob destroyed a fancy new theater.

On January 4th, 1770, the Liberty Boys put up their first Liberty Pole opposite the British barracks in the northern area of City Hall Park. All told, seven Liberty Poles (and one Liberty Tree) have been erected by patriots and destroyed by British on the grounds of City Hall Park; the eighth Liberty Pole still stands there.

On July 9, 1776, at 6 p.m., the newly ratified Declaration of Independence was read in City Hall Park to a public that included George Washington and his troops. After hearing the Declaration, the inspired crowd marched on Bowling Green and toppled the 4,000-pound, gold-plated statue of King George III.

Many souls were freed at City Hall Park when it became the place for executions. The British hanged 250 American soldiers in the park, whose northwestern strip was also part of the African American cemetery. The northeast corner of City Hall Park supposedly still has 15 mostly intact skeletons, most likely dead folks from the old almshouse or jail, buried under a flower bed.

Nathan Hale, America's first spy, was a 21-year-old graduate of Yale who was captured September 21st, 1776, and executed the next day, after his famous last words, "I only regret I only have one life to give my country." He may have been hanged at the north end of City Hall Park by Chambers Street where Jacob Leisler was executed. In 1893 at City Hall, Nathan Hale was immortalized with his first statue; CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, also has a statue of Hale. Frederick MacMonnies sculpted the City Hall statue, giving Hale’s face the knowing look of impending execution.

In 1803, Mayor Edward Livingston laid the cornerstone of NYC's third City Hall, designed by architects Joseph-Francois Mangin (also responsible for the Old St Patrick's Cathedral, still standing) and John McComb Jr. McComb was influenced by the Adams Brothers, who built the 1774 Edinburgh Register Office. The City Hall stairway also pays homage to the Adams Brothers’ staircase at the Glasgow Assembly Rooms. The front and both sides of City Hall were built of white Stockbridge marble, but cheaper brownstone covered the rear section. At the time of its construction, City Hall was so far north of town that its back wouldn't have been really seen by anyone important. The third City Hall was 215 feet long by 105 feet deep and cost just over $500,000. NYC officials began using it on July 4th, 1810, and it was finally finished in 1812.

Fire watch in the City Hall cupola started around 1830. A fireworks display celebrating the laying of the Atlantic Cable destroyed the cupola in August 1856. The 1878 statue called Justice is the third statue situated on the cupola; the first two were made of wood and rotted away.

Tiffany & Young - Tiffany & Young opened on Broadway September 18th, 1837, 10 years after Charles Tiffany ran a country store for his father. The store was in a wood and brick building on the west side of Broadway across from City Hall Park, and its first week’s profits totaled 33 cents. Launched with $1,000 borrowed from Charles Lewis, Tiffany's father, the store first sold stationery and various decorative arts and fancy goods. Unlike other stores in that era that relied on haggling, all the items at Tiffany & Young had clearly marked prices, and Tiffany and his partner John F. Young also had a strictly cash policy; no credit and no bartering. Luckily on January 1st, 1839, the owners took all the cash home with them for the holidays because someone broke into the store and carted away $4,000 of merchandise.

In 1839, the popularity of tasteless baubles spurred the store owners to add crudely made cheap costume jewelry for the first and only time. In 1841, J.L. Ellis became a partner and the Broadway store became Tiffany, Young and Ellis. Four years later, costume jewelry was dropped and real gold jewelry was added because of its escalating popularity. By 1847 silverware and Swiss jeweled watches were also sold. Like his neighbor, P.T Barnum, Tiffany was a publicity genius. He crafted a tiny silver horse and carriage for the wedding of Barnum's little people, General Tom Thumb and Lavinia. In 1853, Charles Lewis Tiffany bought out his partners and renamed the store Tiffany & Company.

In 1870, Tiffany opened the largest jewelry store in the world in a new iron store on Union Square. Much like a museum with all its exhibits for sale, Tiffany’s featured the $18,000 Tiffany Diamond, which was found in 1877 in the new Kimberly mines in South Africa. Now worth over $2 million, the diamond remains the largest flawless canary diamond ever mined. By 1887, Tiffany was called the King of Diamonds when he displayed the French crown jewels. In 1940, Tiffany moved to 727 Fifth Avenue by 57th Street, and 21 years later Audrey Hepburn was immortalized on film as the store’s famously obsessed fan. Charles Lewis Tiffany died in 1902 at the age of 90.

Conrad Vanderbeck - White Conduit House -In the 1700s, Conrad Vanderbeck owned one of NYC's earliest public gardens, and it was located on what would become the NW corner of Broadway and Duane Street. Just south of this old garden was the White Conduit House, built just before or during the American Revolution before Broadway was cut through the area. The White Conduit House tavern had one of NYC's oldest suburban pleasure gardens. The tavern was built on the west side of Broadway (then called Great George Street) between Leonard and Anthony (now Worth) Streets on top of the old Kalckhook Hill. Often used as a meeting house, the White Conduit House was located at the site of today’s 353-357 Broadway until 1800.

Chambers Street Savings Bank - In 1859, the Chambers Street Savings Bank moved across the street to 41 Chambers, where they installed Gayler's great iron chest, then the biggest safe (10 ft. high, 21 ft. wide) in the U.S. In 1843, the Chambers Street Savings Bank was located at another part of Chambers Street, on the old Unitarian Church site, and moved to 67 Bleecker Street in 1856.

Hudson Terminal - Hudson Terminal, the southernmost station on the IND 8th Avenue line, was located at Church Street between Chambers and Vesey Streets. It was situated at the northern edge of the World Trade Center site, under 5 World Trade Center. Under Fulton Street, the IND train would make its turn to continue to Brooklyn.

IND stood for the Independent Subway System, formerly Independent City Owned Rapid Transit Railroad (“ICOS”). The line was always owned and operated by the municipal government unlike the privately operated and jointly funded IRT and BMT. In 1940, the IND merged with the BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation) and IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit Company). The IND Eighth Avenue line opened September 10th, 1932, running from 207th Street to Chambers Street. In February 1933, the IND expanded to Jay Street with the opening of the Cranberry Street Tunnel.

The IND mass transit train lines were the A through G lines. The BMT R train now runs on IND tracks. The V train also runs on the IND F line, and the Rockaway Park Shuttle runs on the A train line.

Lorenzo Da Ponte - Italian Opera House / National Theatre - The National Theatre on the NW corner of Leonard and Church was the home of the Italian Opera House, the first opera house in America. Lorenzo Da Ponte helped open the opera house in 1833. A fire in September 1839 destroyed the National Theatre as well as the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, which was across Leonard Street at the SW corner of Church Street.

Tom Riley's Liberty Pole -Tom Riley's Liberty Pole stood in front of Tom Riley's Hotel at the SW corner of Franklin Street and West Broadway. The 137-ft. pole was erected on Washington’s birthday in 1834 and taken down 24 years later on June 4th, 1858, after decay made it unsafe. The year after it was put up, the Liberty Pole was struck by lightening and had to be replaced by the Democrats.

Many tavern-keepers during the Revolutionary era went out to find pine trees to fashion into Liberty Poles for the front of their establishments. Displaying these signs of liberty was good for business, especially from the local firemen. The taverns and beer gardens near firehouses were sure to have Liberty Poles. Riley's Liberty Pole garnered more notoriety because of the fire department than any other hotel or tavern’s Liberty Pole. Another reason for the attention stemmed from the competitions among the rival engine companies, and the public came to root for different “teams” in these days before organized sports.

Volunteer firemen would compete in a sport called water throwing where, using their pressurized hoses, they would try to throw up a stream of water higher than any other fire squad to decide whose engine had the strongest pumping power. When a fire company would get a new engine, they would come to Tom Riley's Hotel to test its pumping power against the height of the famous Liberty Pole. Jealous of each others’ equipment, the volunteer firemen put their reputation on the line at every friendly competition as well the real emergencies.

Tom Riley's Hotel raised its Liberty Pole the year Boss Tweed became foreman of the Big Six, the nickname of Engine Company #6 that Tweed had long run with. One water throwing tournament on a Saturday at Tom Riley's Tavern was held to see what engine company could send a stream of water over the top of the new pole. Riley would not adorn the Liberty Pole with its usual Phrygian cap until a fireman's stream of water was thrown over the top. No fire company was up to the task, but the Big Six came the closest, just 3 feet short. In 1865, the era of the volunteer fireman came to an end when the Metropolitan Fire District replaced them with paid uniformed firemen.

Unitarian Church -What is now the All Souls Church was first called the Unitarian Universalist Society, founded on April 25th, 1819, in the drawing room of a Mrs. Russel during a service conducted by Dr. Channing from Boston. The Unitarians’ first church was called the First Congregational Church in the City of New York. The cornerstone was set on April 29th, 1820, on Chambers Street between Broadway and Church Street, and when finished, the small white marble church could hold 500 to 600 people. The Rev. William Ware was named pastor on December 18th, 1821.

After outgrowing the crowded old church, the second Unitarian Church was built in 1825 on the corner of Prince and Mercer Streets. It was destroyed by fire in November 1837. In 1839, the Rev. Henry W. Bellows succeeded Rev. Ware (on January 4th), and the congregation dedicated the New Church of the Messiah on Broadway across from Waverly Place. In 1845, Rev. Bellows and the congregation moved to a new church on Broadway between Spring and Prince Streets with a new name, the Church of Divine Unity. During construction of the new church, the congregation met at the Apollo Saloon on the east side of Broadway between Walker and Canal Streets (where the Broadway Theatre would be built). When it became All Souls Church, Herman Melville and Peter Cooper were among its members.

Jacob Finck - Bear Market -Why did butcher Jacob Finck display a bear in his store window in 1771? Well, Finck and his pals killed it after it swam the Hudson from New Jersey. He cut up the bear, and his customers declared it good meat to eat at a time when usually only Indians, hunters and slaves would partake of it. New Yorkers developed a taste for bear meat, and this downtown market would sell any that was brought into the city. Thus, the market became known as Bear Market.

Located on the west side of Greenwich Street between Fulton and Vesey Streets, the market used land donated by Trinity Church (by the former World Trade Center site). It was in business before the Washington Market took over the location around Vesey and Washington Streets.

After the American Revolution, early NYC handbooks joked that Bear Market should be called Bare Market because of its lack of business, few supplies, and the general desolation of this western neighborhood. But traffic increased dramatically after the Erie Canal opened in 1825. The markets off the Hudson expanded up to the meat-packing district, which still retains the old market look. Hundreds of vendors sold hay, wild game (bear included), livestock, fruits, vegetables, and other specialty foods. A million people a day ate meals prepared from the supplies NYC's hotel and restaurants obtained at this expanded market.

Canvas Town / Topsail Town / Fire of 1776 - West Side from the Battery to Barclay Street -During the Revolutionary War, Bear Market was deserted with no business but for some hay sales, so the British cavalry used it as barracks for low-ranking soldiers, who were seen as the troops’ vilest dregs. The Fire of September 21st, 1776, burnt a quarter of the entire area of NYC over two days, creating a whole district west of Broad Street with a neighborhood rising nearly overnight from the smoldering ashes. First called Canvas Town and then dubbed Topsail Town by the resident vagrants and prostitutes, the settlement began with tent huts and shanties created from ships, old canvases securing the remaining parts of burnt walls and old chimneys. Mainly, the British Army and Tory refugees used Canvas Town as the countryside was full of patriots so the British sympathizing Torys fled into the city. Not until 1784 when the British left town, did NYC's grand jury start to battle the problem of the ragtag settlement.

The Fire of 1776 was mostly likely set by unknown early American patriots. George Washington said, “Providence, or some good honest fellow, has done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves.” The fire of 1776 made the British occupation rather uncomfortable.

On Whitehall Street, five days into the seizure of NYC by the British, three resin-soaked logs were set on fire in three buildings. This act of arson at a sailor's brothel, an inn, and the Fighting Cocks Tavern proceeded to destroy almost 500 buildings, including the Trinity and the Old Lutheran Church. Parishioners threw water on the blazes and saved St. Paul's Church but the fire spread further northwest and ended at Barclay Street just before the open land of Kings College.

Most if not all of the town firemen became soldiers who followed Washington into Harlem Heights so unfortunately for the British Navy, they had to act as firemen. Too bad the American Revolution interrupted the municipally owned reservoir started in 1774 according to Christopher Colles’ plans. They might have been able to use the water from the project on White Street that would have spanned water from Collect Pond down the east side of Broadway using hollow pine logs. Some town cisterns were emptied, and many fire buckets' handles were cut, probably a deliberate act on the side of the patriots. And no one heard warnings of the 1776 fire were because all the bells were melted for ammo.

Gerardus Comfort -Gerardus Comfort was a cooper, a carpenter specializing in wooden casks or tubs , and Comfort's dock was by Hughson's Tavern on the Hudson. Comfort's Tea Water came from a spring off Greenwich between Thames and Cedar Streets. Comfort's water was considered far superior to any local public well at the time.

Delacroix -2nd Vauxhall Garden -In 1765, the first Vauxhall Garden in NYC sat on a hill overlooking the Hudson River at Greenwich Street between Chambers and Warren Streets. That year, this former aristocratic neighborhood, at one time a part of Lispenard's Meadows, was invaded by taverns, also known as mead gardens, roadhouses and pleasure resorts. Vauxhall Gardens and Ranelagh Gardens were two of them.

In this garden on June 11th, 1785, the first Catholic church in NYC was incorporated. When they couldn’t get the old Exchange Building at the lower end of Broad Street, the church founders obtained a site at Barclay and Church Streets, and this original St. Peter's Church conducted its first Mass on November 4th, 1786. This, the first Catholic church in NYC, was a simple brick building measuring 48-by-81 ft. In 1806, an anti-immigrant mob attacked St. Peter's on Christmas Eve. This first Nativist American attack on the Irish Catholics was followed by the burning of St. Mary's Church in 1831 and an attack on St. Patrick's original Church (north of Prince Street) in 1835. By the following year, the small decaying church was razed and the current St. Peter's was built at double the size.

Taken over by a Frenchman named Delacroix, the second Vauxhall Garden opened in 1798 between Grand and Broome Streets and Mulberry and Lafayette Streets on the former site of Bayards Mound (Centre, Broome, Mott and Grand Streets). Vauxhall Gardens featured flying horses (a precursor to the carousel and the merry-go-round), mead booths, concerts and fireworks at night.

NYC's third version of Vauxhall Gardens, built in 1804-1805, used the Sperry's Gardens site, across from the La Grange Terrace (Colonnade Row). This garden stretched north to Astor Place on the east side of Lafayette Street. Broadway and Bowery, from 4th Street to Astor Place, was actually given the name Vauxhall because of the Gardens there. Delacroix leased the land for the third garden from John Jacob Astor, who bought Sperry's Gardens in 1804. He bought it from Swiss physician Jacob Sperry, who had created NYC’s first botanical garden at Lafayette and Astor Place.

John Jacob Astor bought his first tract of NYC land in 1789. In 1805, Astor and partner John Beekman bought the Park Theatre. In 1828, Astor paid $101,000 for the City Hotel, and then he built the Astor Hotel in 1836. Astor died in 1848, the richest man in America who made $20 million from furs, opium, shipping as well as real estate.

Greenwich Street got the first elevated train track in 1868, thus launching America’s rapid transit system. Running on tracks constructed 30 feet over the street, noisy trains powered by steam engines would shake buildings and spew oil, cinders and ashes. Soon, elevated tracks cast more shadows over Third, Sixth and finally Second Avenues. The last el in Manhattan, the Third Avenue line, was demolished in 1955.

Washington Market - Washington Market at the foot of Fulton Street, the most famous market in NYC's history, opened in an indoor facility with a city-built facade on December 16th, 1832, by the old site of the Bear Market. The original Washington Market was an open-air bazaar full of fish and country market goods, which opened in 1813 between Washington and West Streets on one side and Vesey and Fulton Streets on the other. It was first called the Country Market, then the Fish Market, and the Exterior Market. The market also had a bell tower for fire warnings on the high ground at Vesey and Washington Streets.

The indoor Washington Market had over 800 vendors for wild game, livestock, fruits, vegetables, hay and specialty foods. A million people a day in NYC ate meals prepared from the footstuffs the hotels and restaurants acquired from the market. For many years, it was the largest wholesale produce market in the U.S. The world famous Washington Market was removed to make room for the World Trade Center in 1967.

West Washington Market, an subsidiary of the Washington Market, was first erected by NYC on the bulkheads and wharves opposite the original market by Dey and Barclay Streets. In 1889, West Washington Market moved to ten two-story brick buildings at the present day meatpacking district by 13th Street between Washington and West Streets, and between Gansevoort and West 12th Streets. This area got hot when the Erie Canal opened in 1825, and the southerly markets off the Hudson expanded up into it. NYC set up this second West Washington Market as ten two-story brick buildings that had the piers to their back and West Street in the front (the Sanitation Department is there today). The West Washington Market specialized in meat and poultry but also dealt great quantities of fruits and vegetables. It was demolished in 1950, and the site was taken over by trash barges of the Gansevoort Garbage Terminal until 1981.

The West Street Building -The West Street Building, a 23-story, Gothic Revival-style building at 90 West Street (1905–07), originally had lavish plans for the lobbies that architect Cass Gilbert was told to simplify. The building was topped by the Garret Restaurant, which promoted itself as the highest restaurant in New York. The building still stand at the southwest corner of Ground Zero, and two people died in the elevators during 9-11.

Battery Park City / World Financial Center - The 92-acre Battery Park City was created from 25 acres of landfill dug out to make room for the former World Trade Center Towers and from sand dredged out of New York Harbor off Staten Island. The 8-million-sq.-ft. World Financial Center took six years to build. The four granite and glass towers are topped by copper domes. Built on a landfill where the famous free version of the No Nukes Concert took place, it now offers live music in its Winter Garden complete with palm trees. The World Financial Center is the world headquarters of Merrill Lynch and American Express.

Gateway Plaza - The six apartment houses that make up Gateway Plaza (the only building in Battery Park City not designed under the Master Plan) was the first building and first 1,712 units built there. Created by Jack Brown and Irving E. Gershon, Gateway Plaza was begun in 1982 and finished in 1983 -- and fully occupied by the end of the year. The first person living in these three 34-story buildings was Brian Babbit, who moved to Staten Island by Sals my favorite Pizza Place. Gateway Plaza was badly damaged during 9-11, and the complex was closed for many months.

Brian Tolle - The Irish Hunger Memorial -The Irish Hunger Memorial commemorating and raising awareness of the Great Irish Famine (1845-1852) was dedicated July 16th, 2002. Sculptor Brian Tolle built the memorial to a million victims to look like a fieldstone cottage on a hilly Irish farm, bringing it over in pieces from Ireland. Each stone on the slope is from one of Ireland's 32 counties. Landscape architect Gail Wittwer-Laird added grasses, plants and wildflowers to the project, located on a quarter-acre site at the NW corner of Vesey Street and North End Avenue in Battery Park City. This historic sculpture was completed for $5 million.

Ah Ken's Cigar Stand -In 1858, Cantonese tobacconist Ah Ken set up his small cigar stand on Park Row by the City Hall fence while living in a house on Mott Street. His cigars sold for 3 cents each. This businessman was the first Chinese immigrant to permanently stay in NYC (well, besides the murderer Quimbo Appo, a China-born sailor turned tea merchant, who came to NYC in the 1840s, and was famous for his interracial marriage and called the Chinese devil man). Ah Ken also became landlord to many Chinese immigrants who came afterwards. William Longford, John Occoo and John Ava were cigar makers who formed a monopoly after Ah Ken started the cigar craze in Chinatown.

The first Chinese gangster who came to NYC was Cantonese businessman Wah Kee. Wah Kee came from San Francisco in 1866, and sold fruits, vegetables and curios until he realized he could make more money above his store with gambling and opium. Wah Kee's sucess, by 1880, led many more Chinese immigrants (especially Cantonese) to NYC's Chinatown. Many of the Chinese who worked on the transcontinental railroad found themselves unwelcome on the West Coast so they settled in NYC. The first freight cars from the West Coast arrived in New York in 1870. By 1900, more than 6,300 Chinese residents were living in Chinatown, which consisted of Mott, Pell and Doyers Streets. In 1899, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion acts, which banned their naturalization into America.

Thanks to Wah Kee, the Chinese Tongs made Chinatown the opium center of NYC.

John Roebling - Brooklyn Bridge - The East River was one of the craziest stretches of saltwater navigable on earth. NYC's large harbor made this island surrounded by docks the greatest city in the New World. Technically not a river, the East River is a turbulent tidal strait. Bad weather always stopped passage across; people and parcels were often delayed, and goods spoiled. Brooklyn had 400,000 residents when the idea of a bridge was first proposed to the State Legislature in 1802.

John Roebling, owner of a wire-rope company in Trenton, was famous for his bridge designs over the Delaware (1848), Niagara (1855), and Ohio (1867) rivers. While impatiently waiting for the Fulton Ferry, Roebling worked out the plan for a suspension bridge with four steel cables and giant granite towers. In 1855, when he proposed building the first bridge over the East River, he envisioned it an artistic national monument as well. Roebling and Wilhelm Hildenbrand completed plans for the bridge in a remarkable three months.

The cold reaction from NYC officials led Roebling in 1867, to The Brooklyn Eagle, whose publisher William C. Kingsley had political connections. New York State Senator Henry Murphy, also a former mayor of Brooklyn, drafted a bill to allow the bridge to be built by a private company. In 1866, the construction bill passed the New York State Legislature.

The New York Bridge Company was formed and incorporated in 1867, with $4.5 million in funds available. The money was raised from an enabling act that Brooklyn contributed $3 million, while Manhattan added its $1.5 million. Roebling’s design was finally approved in June 1869 when the City Council got the thumbs up from the Army Corps of Engineers. Congress passed a construction bill and it was signed by President Ulysses S. Grant (the eighteenth president of the United States). The last legal hurdle was overcome on June 21st, 1869, when the War Department approved the Brooklyn Bridge project.

On July 6th, 1869, the Fulton ferry crushed John Roebling's foot, while he was standing on a cluster of piles at the outboard end of the Brooklyn's Fulton Street slip, where he was trying to determine the location of the Brooklyn tower. His foot was caught between the collapsing piles and the fender rack, and the injury infected John's toes to the point of amputation. Toeless John Roebling refused further medical treatment except for water therapy (where water was continuously poured over the wound). The accident gave the 63-year-old Roebling incurable tetanus (“lockjaw”), and his blood was poisoned with gangrene, so in just a few weeks after his injury became fatal on July 22nd, 1869.

His oldest son (out of nine children) Washington A. Roebling took over the project as chief engineer. The first $3.8 million was spent just purchasing the land for both approaches to the bridge. The ground for the Brooklyn Bridge was broken on January 3rd, 1870, but the foundations took three years to dig. Workers had to endure being placed into airtight pneumatic caissons sealed with pine tar and almost a half-block wide. The caissons were sunk into the East River by putting stones on top of them, which eventually created the foundations. To anchor each of the four cables, four 16-by-17-ft. cast-iron anchor plates (21 ft. thick) were constructed, each weighing 46,000 pounds (23 tons). Workers using shovels and buckets cleared away layers of silt under the East River until they hit bedrock. It was the first time dynamite was used to construct a bridge.

Workers paid $2.25 a day had to dig 44˝ feet below the river on the Brooklyn side before they hit bedrock. More agonizing was the fact that they had to dig twice as deep below the Manhattan side, 78 feet below the silt and quicksand. On October 12th, 1872, the first worker died from caisson illness. Soon over a hundred workers were unable to work. Finally, when two more of the sandhogs died, Washington Roebling decided to stop digging; compacted sand was good enough. History proved him right, and recent tests show he was still 30 feet away from bedrock on the Manhattan side.

Caisson disease killed 20 workers and left 35-year-old Washington Roebling paralyzed. It’s caused by the altered nitrogen levels in the blood from the changing air pressure. Washington's wife Emily made daily visits to the bridge to oversee the operation, helping Washington direct the construction of the bridge from their new Brooklyn Heights home overlooking the site. Emily studied mathematics, calculated the curve of the wires, checked the strength of materials and supervised the project for the next 11 years. Roebling used field glasses and a telescope to watch the progress.

Once the foundations were done in 1873, it took four years to construct the anchorages, and have the four massive steel cables supported by the two 273-ft. Gothic granite towers. Only Trinity Church was higher than these twin towers, which held the weight of the cables downward pressure.

The Brooklyn tower was finished in May 1875; two months later, the Manhattan side was completed. The neo-Gothic towers are made of limestone, granite and Rosendake cement. In August 1876, when the two anchorages were linked, a mechanic named Farrington crossed the East River on a chair tied to the rope. Until the Brooklyn Bridge project, weaker iron wire was used for suspension cables in bridge construction, Roebling introduced the use of steel for his four cables. Roebling's invention and manufacturing of steel wire cable changed the suspension bridge business and made this longer bridge possible.

By February 1877, a temporary footbridge 135 feet over the East River was finished, and work started on spinning the four cables. Over 14,400 miles of wire were used to spin these four 15˝-inch cables consisting of 19 strands each, which added up to 21,432 steel wires in each cable. When finished, the strength of each cable could now hold 11,200 tons.

At 6,016 feet (including approaches), Brooklyn Bridge (known at the time as the Great East River Bridge, or Great Bridge) was not only NYC's first bridge over the East River but also the longest suspension bridge in the world. It opened on Queen Victoria's birthday May 24, 1883, in front of 14,000 invited guests. Emily Roebling was given the first ride over the bridge with a rooster (a symbol of victory) in her lap. Governor Grover Cleveland, Mayor Franklin Edison, and President Chester Arthur met Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low at the Brooklyn side tower. President Arthur continued on to Washington Roebling's home after the event.

The bridge opened to the public (150,300 people on the first day) at 2 p.m. May 24th, 1883, bringing in the Brooklyn Bridge’s first $1,503. The bridge was opened to vehicles at 5 p.m the same day, 1,800 vehicles crossed on the first day at 5 cents a car ($90 more)

Getting across the Brooklyn Bridge was just a penny toll for pedestrians until 1910 when it was made free, Soon the bridge had elevated trains (September 1883), trolley lines, horse-drawn vehicles and livestock stomping across it. On Memorial Day, May 30th, 1883, one week after the Brooklyn Bridge opened, a woman on the Manhattan steps fell after a large gust of wind, and a scream started a rumor that the bridge was collapsing. Panic crushed 12 people to death, while three dozen more were seriously injured. The following year citizens’ fears that the bridge was not strong enough were squashed when P.T. Barnum took 21 elephants across the bridge (led by the famous Jumbo).

The BRT elevated trains on the bridge were stopped in 1948, and the streetcars took over their tracks before they too were removed in 1950. Poets and artists had a new inspiration, but 27 people died during its 14 year construction; its creator John Roebling included.

The one-mile Brooklyn Bridge was finished in 1883, which helped made Brooklyn part of NYC by 1898. With Tweed as one of the six executives of the Brooklyn Bridge company, it was amazing it only cost $15 million to build. Contractor J. Lloyd Haigh switched the wires used over its stone towers leading to a $9 million renovation in 1948.

Monkey Hill was on William Street by the second Printing House Square on Park Row, which was once called Newspaper Row. Monkey Hill is now under and just north of Manhattan side of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Alfred Bult Mullett - The City Hall Post office (Mullet’s Monstrosity) - The City Hall Post office (Mullet’s Monstrosity) opened in 1878. It was an elaborately colonnaded, French Second Empire baroque structure with a mansard-roof that looked like a wedding cake. No one seemed to like Alfred Bult Mullett’s post office at the triangular tip of City Hall Park, and as early as 1920 the city tried to demolish it. Mullet’s Monstrosity was finally torn down in 1938 to make the park nicer and beautify City Hall for the 1939 World’s Fair visitors.

The first letter from America was postmarked August 8th, 1628, from Manhattan in New Netherland to Hoorn by North Holland, in the Netherlands. In 1633, Richard Fairbanks' tavern in Boston became the first official site of mail delivery, 40 years before a mail run started between NYC and Boston. Boston set up the first organized postal system in the American colonies in 1677.

Before the public mail service started, before any post offices were opened, Dutch schoolmasters delivered invitations to funerals, and Indians were used to send messages into the interior of the New World. These Indians traveled on foot and canoe, and were paid only when they returned with a response letter. After 1672, trusted Indians carried the mail to Albany in winter. Under English rule, Vlieboat skippers took mail up the Hudson during the summer months, up to Albany (where Fort Orange was). These NYC's Dutch vlieboats (the English called them flyboats) took 10 days to three weeks for the one-way trip. The foot post workers were used in the winter to deliver mail north from NYC to Albany, when the river froze over they skated most of the way.

In good weather, the first regular NYC horseback mail to Boston (which started in 1672) took almost a week on this once-monthly trip. Riders had to stop to sleep and eat so if conditions were good they could do the whole 230 miles in a week. Governor Francis Lovelace announced the NYC to Boston horseback mail run on Dec 10th 1672, it was called monthly but went over three weeks, the first mail was delivered by January 22nd, 1673. It took the post rider two weeks to do the run from NYC to Boston. Old Boston Post Road is part of today's Route 1.

Jacob Wrey Mould -Mould Fountain - Southern triangle of City Hall Park by Broadway and Park Row - In 1871 the old Croton Fountain was replaced by the ornate granite Victorian Mould Fountain designed by Jacob Wrey Mould. Installed in front of the old Post Office, it was referred to as Mullet's monstrosity. When they were first planning to tear down the post office in 1920 (it didn't happen until 1938), they moved the Jacob Wrey Mould fountain to Crotona Park in the Bronx. The Delacorte Fountain replaced it, until Rudy Giuliani brought it back in 1999. Now lit by four gas candelabras and underwater lighting, it makes a night time trip to City Hall Park worthwhile. The homeless Jack London, who once slept in City Hall Park, would have enjoyed its waters.

The 1873 Bethesda Fountain (also called the Angel of the Waters) in Central Park was created by Emma Stebbins and co-designed by Jacob Wrey Mould. Stebbins was the first woman allowed to create a major NYC public work. Its four cherubs represent Peace, Health, Purity, and Temperance. The late 1960s brought so many peaceniks to its waters that Newsweek in the late 1960s called it Freak Fountain. It was constructed in Central Park to celebrate the completion of the Croton Aqueduct in 1842.

Major William W. Leland - The Clinton Hotel - The Clinton Hotel at 5 Beekman by Nassau Street was named after George W. Clinton, but it was made famous by the Leland family. The first Leland who worked at the Clinton was Major William W. Leland, but he died on August 9th, 1879 from eating unripe cherries when he was 59. Major Leland was best known for being an earlier proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel next to Niblo's Theatre on Broadway and Prince Street. William's dad Simeon Leland Senior was the Donald Trump of his time. Simeon in 1820, first opened a store in Landgrove Hollow, Vermont, a few years later he also opened the Leland Coffee House in the same town. Simeon Leland Senior started the family hotel business during the Revolutionary War by building and managing a hotel in Vermont, which was the headquarters of Ethan Allen's Green Mountain Boys.

Preston Henry Hodges got his father Preston Hodges to buy the Clinton Hotel in 1832, they remained business partners until 1839. Preston Henry Hodges then took over the Carlton House and ran that hotel until 1857.

Simeon Leland Junior became proprietor of the Clinton Hotel, but he sold it to his brothers Charles and Warren. Brothers Charles and Warren Leland controlled the Clinton Hotel for more than 20 years. Simeon Junior's son, Warren F. Leland was 16 years old when he started working for his uncles at the Metropolitan Hotel, which was also owned (since 1852) by his father Simeon Jr. and his brothers (Charles, William and Warren Leland).